The voyages and scientific expeditions of this young Brazilian woman, born in São Paulo but who continued her career as a naval architect in France, unfold stories of the North Pole and her transatlantic crossing, which she chronicled in a series of books.

The story of this adventurer who pioneered the first Latin American woman to cross an unexplored passage connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through northern Canada, Greenland, and Alaska.

Tamara Klink

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” That’s the first thing you think after chatting with Tamara Klink for a long time. The 28-year-old writer and sailor is the daughter of Amyr Klink, a Brazilian explorer, sailor, and writer who circumnavigated the Antarctic continent and was the first to cross the South Atlantic from Namibia, Africa, to Salvador, Brazil, aboard a small rowboat for almost 100 days in the 1990s. So, upon his return, when this little girl listened to her father’s stories while waiting for him at the port with Marina Bandeira, her mother—a talented photographer—and her two sisters, or knitted at night lulled by those tales of stormy seas teeming with whales and seals, surrounded by towering icebergs, she never imagined a future far removed from that ocean.

Tamara Klink began planning her own journeys when she was twelve years old. The desire—and the boat—arrived soon after when she crossed from Norway to France on her first long voyage aboard an old wooden sailboat. In 2020, she dared to cross the Atlantic solo—from France to Recife, Brazil—a journey that catapulted her to the top as the first young Brazilian woman to sail in her country. Later, she became the first woman to spend the winter alone in the Arctic Circle, during nine months of hibernation. On that same voyage, in September 2025, she also ventured to navigate the treacherous Northwest Passage for 45 days, a 6,500-kilometer stretch from Greenland to Alaska connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through icy waters.

But sailing wasn’t the only thing she inherited from her father: her reading of explorers and her love of writing also took her to new worlds. In 2010, she published the book *Vacations in Antarctica*, along with her sisters Laura and Marina Helena—which was included in the curriculum of many Brazilian schools—followed in 2021 by two more books, *A Thousand Miles* and *A World in a Few Lines*. In 2023, she published *Nós: O Atlântico em Solitário* (not yet translated into Spanish), a book that recounts her solo crossing of the Atlantic in 2021. “When I’m sailing, alone, in the middle of the ice, I have a feeling that grips me: I’m entering those stories I heard when I was little, that my father told us when he came back from his trips. I wanted to know what it was really like,” she says, now, just hours away from spending Christmas with her parents and sisters in São Paulo, Brazil.

How did you get started with sailing?

I first became fascinated by sailing because of the stories my father told me. He spent many months at sea, and when he returned from his voyages, my mother, my sisters, and I would go to the beach to watch him arrive. His voyages were very long: sometimes three, four, five months, even a year. We adored his stories, and I longed to travel someday to see the giant animals that swam beneath the ship, which he described to us in great detail. He also told us about birds that could circle the globe simply by flapping their wings, gliding, or that swam like whales. He also described immense castles, churches, and cathedrals that were icebergs, built of water, floating on the sea.

I wanted to explore that magical world. When we were children, we also went to Antarctica for the first time: I was eight years old, and my sister was five. We realized that all the stories he told us were real, and I couldn’t live the way I had before exploring that entire continent. That’s why I also started reading a lot of books; it was a way to keep the dream alive. When we were little, we also sailed Optimists: my mom took me to the lessons, but I wasn’t very good at it. I didn’t really connect sailing on that small reservoir (in São Paulo) with the trips my father took. I always came in last. I didn’t like it much, but it was important because, as children, we weren’t allowed to take many risks or we were forced to stay put. But on that boat, the girls and boys were on equal footing. We all had a right to feel danger, to take risks, to experience autonomy, to sail as far as we could, to cross that lake with our own will and knowledge, in that small vessel, which was very liberating.

What doubts or fears arose at that time?

One of my main concerns was whether I could become that sailor, that “seaman” I knew, because I wasn’t a man (laughs). Later, when I had to choose a course at university, I went into Architecture with the idea of building real projects. In other words, we start with theory—and dreams—to make them a reality. I thought that this degree would give me a toolbox of skills to later become a sailor.

I did my first studies at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, and then I lived for almost seven years in northern Brazil. I also continued my studies at the Naval Architecture School in Nantes, France, thanks to an academic exchange program. In France, I finally met women who sailed and traveled. That was very important because it seemed impossible to me. The possibility of meeting other people my age who sailed, or even the same authors I had read, also broadened my horizons.

Is it true that your first sailboat, the Sardinha, cost the same as a bicycle?

Yes, I think I held onto that experience and feeling from the Optimist, and when I bought my first sailboat, a very old boat, in Norway, I spruced it up for sailing. It was during the pandemic, in 2020. It was a Magic, designed by a Swedish naval architect, from 1984. I was 22 years old: I sailed from Norway to France. I didn’t plan to go any further than that.

My idea was to build a new boat to cross the Atlantic, which I was going to design myself, but I realized that I already had a sailboat that was perfectly suited for that crossing. I didn’t need a new boat, which I would have had to build, secure sponsorships for, and which could take years. So I decided to go with my own boat, on a journey that had many surprises, with stressful moments and other very good ones because I met many people in every port, made friends, and learned a lot about myself, about the sea, and about the boat.

Why is the sailboat called Sardinha?

My grandmother chose the name for the boat: she said it was a small boat, one that no one expected much from, but that could cover great distances. But above all, because sardines are never alone; they always swim in groups.

How did you decide to travel to the Arctic Circle?

I really enjoyed crossing the Atlantic. So, when I arrived in Paraty after that voyage, I decided to take the longest trip I knew of up to that point, a journey through time, where I could spend as much time as possible at sea. What I thought I wanted to try was a journey through the seasons in the Arctic, where I could be ‘trapped’ in the frozen waters of the Greenland Sea.

That possibility implied a high degree of self-sufficiency in terms of food, heating, and the ability to complete the journey, right?

You were the first woman to spend the winter completely alone at the Pole.

There isn’t a word for this in Spanish or Portuguese, but in French or English it’s something like hibernation. My idea was to go to a very cold place, where the sea is frozen, and stay for eight months: I loved it (laughs). It was also very dangerous because it was easier to die than to try to survive in those places. The truth is, I prepared a lot beforehand: on my boat, I was at home.

I lived for two years before setting sail (on the Sardinha 2, a 32-foot steel sailboat) from France to Aasiaat, in Greenland. I had enough food for the whole winter, which was practically vegan, for example, with lots of seeds, which I could also germinate. Sometimes I also fished, because I realized that with the leftovers, I wasn’t leaving any waste if the foxes ate it.

In one episode, I saw you encounter a polar bear that tried to climb the sailboat’s ladder. But I hadn’t heard you mention foxes.

Yes, there were many white and black foxes that came near my boat looking for food. Sometimes I left them fish scraps, but other times it was the very fish I was planning to eat (laughs). Sometimes they stole my thermometers: I lost all the ones I had for measuring the temperature! Other times I found small objects from my boat scattered around the deck: a loose rope that wasn’t there or the camera cover strewn about by these very intelligent, very alert animals—I wasn’t so much (laughs). There were also many crows, small, feathered pigeons, and even seals. There weren’t so many animals in the middle of winter: it was all very quiet.

Beyond the icebergs and the instability of the climate or the ocean currents, what impressions did you have, throughout the journey, regarding climate change and its impact on the species of the region?

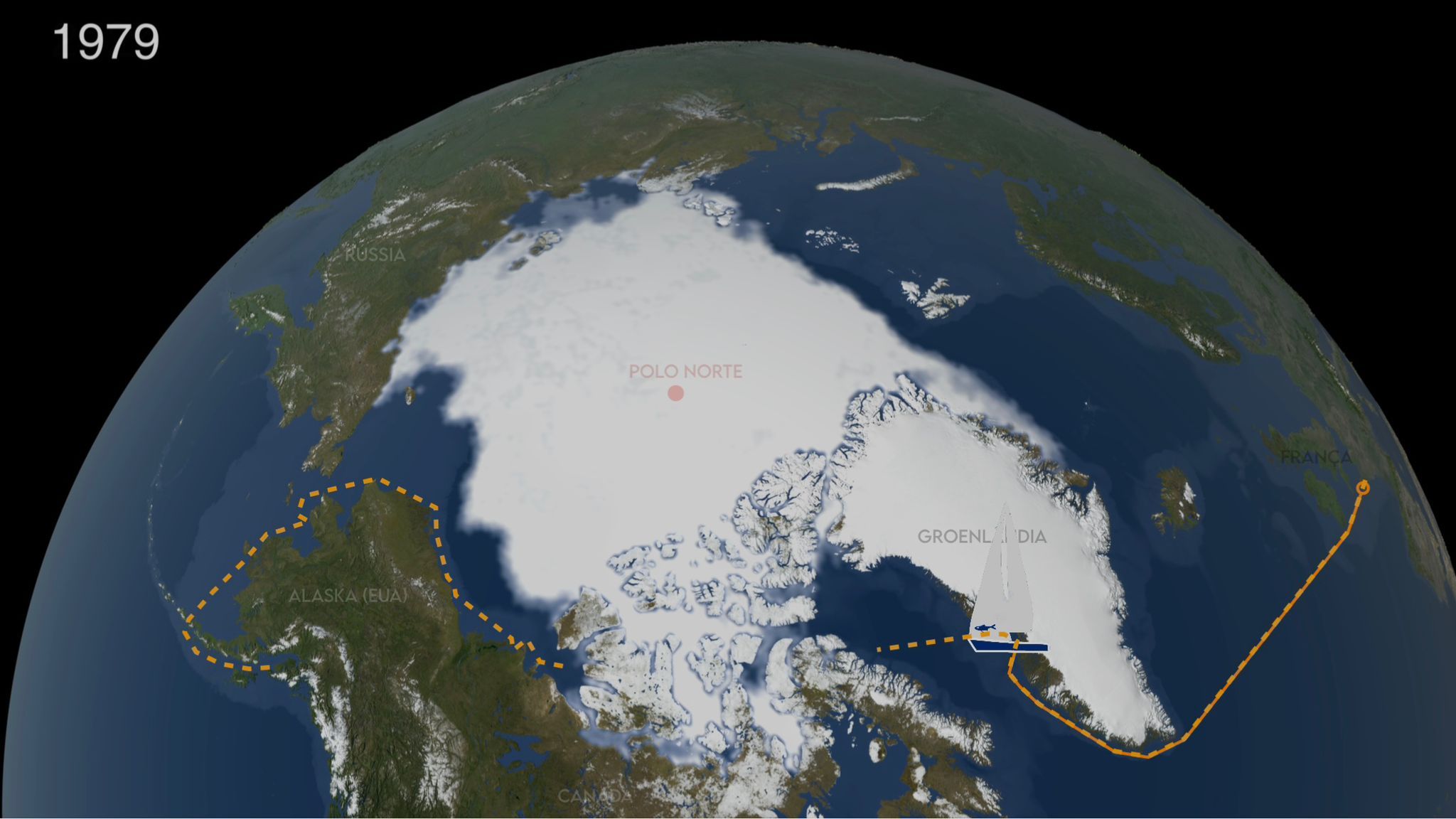

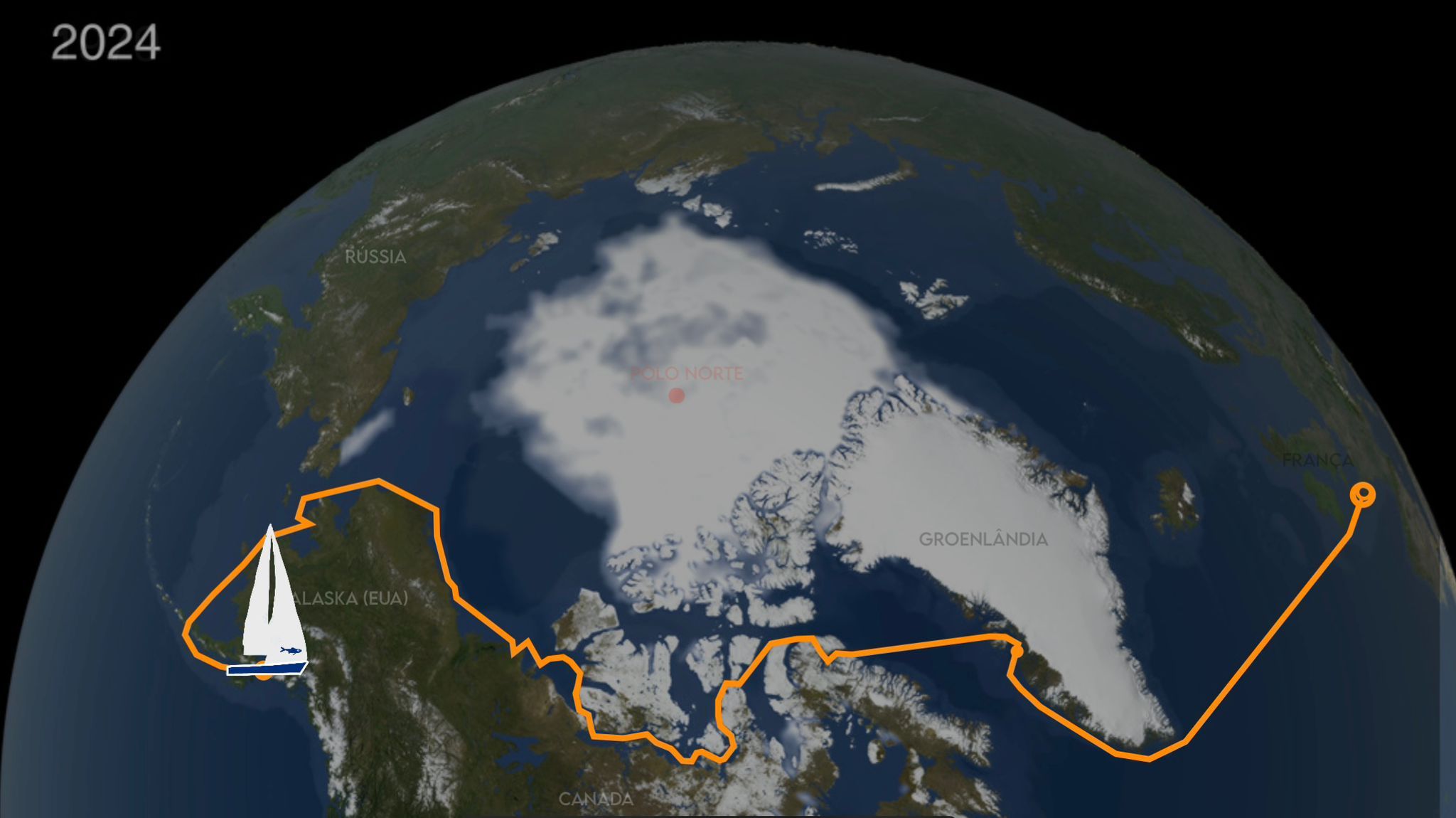

Is it true that only 9 percent of the route had sea ice, unlike some 30 years ago when icebreakers were needed or crossing this strait was very difficult?

In other words, the passages are now open for longer navigation: before, it might have taken years to cross, but now I did it in about 45 days, encountering sea ice for only five days. One of the most important accounts I read about this passage was by Roald Amundsen, who completed it in 1905 over three full years (he was the first navigator to complete the Northwest Passage, which has always been very challenging). It took me 60 days in total until I reached the first outpost.

I imagine that nautical charts, being such an unexplored region, are also very unreliable. How did you handle this?

Nautical charts are very unreliable, absolutely. It’s a region where—so far—there aren’t many ships, so mapping the seabed must be very expensive. Furthermore, for a large part of the year, the surface is covered in ice, although it’s thinner and doesn’t last as long as it used to. There are many uncharted areas, where there are only narrow channels with possible routes. We can never see exactly what’s on the seabed, so we navigate using navigational instructions, which are the texts that were used before and say things like, “Be careful because the currents here are very strong, there are no tide tables, and it’s all very dangerous.” So we have to assess the situation based on our own eyes and knowledge, take measurements, and determine how to proceed.

It’s very technical navigation: I noticed that other boats had many problems, and yet I felt very safe. I also had a lot of fun, although—of course—I encountered difficult conditions, but nothing completely new because I now have some experience as a navigator. This was the longest voyage I’ve undertaken so far.

How did you cope with time and loneliness during these months without human contact?

It’s a type of sailing I wouldn’t recommend for beginners, because we never slept more than 20 minutes at a time: I’d wake up and check outside for icebergs, rocks, other boats, then sleep for another 20 minutes. Sometimes I couldn’t even go back to sleep because there was so much to be aware of. Now I think I’m more used to it because I’m more aware of my sleep patterns and I can regulate them a bit.

I’m not so easily surprised anymore, but of course I’m still a beginner: I suppose I always will be, because the sea is always different, storms can be bigger, or I can encounter more precarious situations, although I never want to expose myself to greater risks than necessary and I always try to protect my body because it’s my instrument of work and an important machine for the boat itself to function. I can’t get anywhere if my boat can’t.

What did your father say when you told him about your solo sailing plans?

And how do you handle the pressure of being the daughter of such a renowned figure in sailing?

When I was twelve, still a child, I asked my father if he would let me travel alone, and he said yes. I asked if it could be on his boat, if he would lend it to me, if it was available for me to sail alone, and he said no. His thinking was that if I wanted to sail, I should get my own sailboat and build it the same way he had built his. He believed that if I wanted to sail, I also had to forge my own path. So I had to learn in a different way. Today I can recognize that my father opened many doors, not only for me, but for many sailors in Latin America who dream of doing difficult things. He was very inspiring to many people who read his books or discovered his voyages. In many places around the world where I’ve been, I’ve met sailors who had read his books or kept them on their own boats. When I was little, I thought all fathers were like that and that they often went to Antarctica, for example, but when I grew up, I realized that wasn’t the case.

I truly realized that my father had expanded the boundaries of both the impossible and the possible. Those things that were practically impossible became part of my dreams thanks to him. At the same time, when he told me he wasn’t going to help me with money, the boat, or contacts, he also gave me the freedom to forge my own path, with my own successes and failures, which is essential for learning. I learned to make decisions on my own because there was no one else on the boat to ask. That’s why I think building a project is part of a sailor’s training: it’s such a difficult stage that, once we overcome it, sailing seems very simple afterward (laughs). In projects, you have to deal with routes, deadlines, lack of money, people who tell you it’s all impossible, that you’re not capable, bureaucracy, and visas between countries, when sailing is just the sea, your body, and the boat.

And what’s your relationship like with your parents when you’re traveling? Do you let them know when you arrive safely? I mean, thinking especially about your father, who knows about the dangers or difficulties you might face.

I generally don’t like being in contact much; I only use a satellite device to send short messages. I don’t communicate much with my parents while traveling because they might get too worried and wouldn’t be able to help me solve problems. So I only communicate with people who can truly help me in a situation without strong emotional ties.

Based on your own experience, what do you think is essential for solo sailing? What elements do you consider indispensable?

A stopwatch, a clock, to wake me up during those twenty minutes of sleep. I also need comfortable clothes and a journal to write in case I die. I think it’s important to have a record of what happened. Sometimes, when we’re alone for a long time, we start to have repetitive or negative thoughts. Sometimes a little paranoid or desperate. But when I write, I no longer have the right to be a victim; I’m forced to be the protagonist of the story and to see my possibilities for regaining control of the situation. It helps me a lot, which is why I think a notebook is important.

For everything else, there are substitutes: for example, the autopilot failed me, and yet a small book showed me how to set the sails a certain way to keep the boat balanced. I know it’s possible nowadays to navigate in other ways with a sextant, guided by the stars, even in coastal navigation. But, besides all this, it’s very important that no water gets into the hull (laughs).

Furthermore, nowadays when we prepare for a voyage, perhaps the most difficult part is the visas, the documentation, the bureaucracy; they aren’t equally accessible to everyone. A French passport doesn’t have the same value as a Brazilian or Argentinian passport, so we spend a lot of time battling paperwork storms (laughs), and then, when we’re actually sailing, everything seems much easier.

The relationship between navigation and literature is very old. Why do you think this link between writing and the sea is so important? Or what motivated you to write books that portray these voyages?

It’s a very important relationship, because I believe that without literature, a large part of sailing would be meaningless. Voyages are enriching because they stem from the same imagination. We spend many days in the middle of the sea, with nothing around us, and through literature we connect with other people who made that same journey in another era, many years ago, or in a landscape perhaps similar to this one. The experiences of others also help us realize that the difficult situations we are facing are not so complicated and that the good ones are perhaps better than we had imagined, because reality is always more complex than imagination.

Books allow us to imagine, and desire is the only reason that makes us sailors: there are no logical reasons to undertake a voyage; it is uncomfortable, dangerous, slow, and expensive to go from one point on the planet to another. However, if we do it, it is because we have a desire, and that desire is born solely from the imagination. For me, literature is still one of the most powerful arts for expanding that imagination: much more so than film, television series, videos, photography, or painting. As soon as we read something we have the impression of being in the place, with our own internal references, we create a world or a whole universe.

So what happened when you started writing your own books?

Sometimes I would get frustrated: the word “white,” for example, wasn’t enough to describe what I was seeing. The icebergs, the ice, the snow. Words for the sun or the smells aren’t sufficient: that vocabulary felt inadequate for everything visible. Often, I wanted to contain the world I observed with words, and I was always dissatisfied with what I managed to put on paper.

Furthermore, I believe it’s the duty of all sailors who have the privilege of fulfilling their dreams and sharing them, to document that experience, because many people don’t have the opportunity to dream or lose that desire when they grow up. So, this is a way of thanking the world for the opportunity to be at sea, to do what I love most in life, and which is also a very powerful tool for changing people’s lives.

Every day I receive messages from people who, after reading one of my books, tell me they’ve decided to move to another country, have children, break up with their boyfriend, pursue a doctorate, take a trip, or change jobs. I didn’t tell anyone; I simply shared my own journey. But they need a little encouragement to take the plunge: for desire to finally conquer fear.

What are the main books that influenced you?

The first is a French book by a sailor, Gérard Janichon, initially published in three volumes. It tells the story of two 18-year-old friends who, in the 1960s, decide to set off to circumnavigate the globe. They don’t have much money, but they are young. So they outfit a small wooden boat for the voyage, facing many difficulties but with a great determination to go far. They eventually complete the journey, which takes five years.

I think it’s a book that portrays the power of naiveté and youth, but it also speaks of a great friendship and a love of the sea. It seems to show us how difficult things can be, but if we knew everything beforehand, or what it entails, we probably wouldn’t even try. It also speaks of a world that has changed a great deal, of borders, of countries.

Finally Tamara, what are your plans for the next few weeks?

Among my most immediate plans is the completion of two books already underway, one about winter in the Arctic and the other about the Northwest Passage, which will be launched in Brazil and France for now. I also have some solo projects, but I prefer not to share anything about them until I’ve actually carried them out, or to only talk about what I’ve actually done.

In a couple of weeks, I’ll be leaving with an expedition to Antarctica, with a group of sailors, to investigate krill fishing. Many countries are using it to feed salmon (an increasingly large industry), which disrupts the entire food chain and is very destructive to the marine ecosystem, affecting animals like whales, penguins, and seals. These animals are beginning to suffer from food shortages, so we’re going to investigate what’s happening, along with a group of scientists, divers, and journalists, to show what’s going on with this issue.

Links:

Livro Nós : o Atlântico em solitário

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tamaraklink?igsh=MWFlOXYxb3F2Z2VzaQ%3D%3D&utm_source=qr

From “Navegantes Oceánicos”, we thank Tamara Klink for sharing her experiences as a sailor and her great adventures with our readers, such as crossing the Northwest, sailing the Atlantic solo, and wintering in the Arctic.

With all our admiration, we wish you the best of luck in your future adventures and much success with your book publications.