The voyages and scientific expeditions of this geographer, born in Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego—in the southernmost part of Argentina—allow us to explore new routes: from discovering the Falkland Islands to traveling up Patagonia towards Brazil. It is the story of an adventurer who traverses the icy and inhospitable landscapes of the southern seas.

The piano wouldn’t fit on the boat, so he brought a melodica: that flute with a mouthpiece and keys that blows and blows—like the wind of the Beagle Channel, constant, unpredictable—with melodies that surely attract dolphins, seagulls, or cormorants. That was the first image I saw some time ago of Pic La Lune—playing, or rather, caressing the moon, in French—with a great musician from Argentina, Nico Sorín, who, in the middle of an ocean of icebergs and with the snowy peaks of a glacier piercing the horizon, strummed melodies on the bow of this sailboat with its vermilion hull.

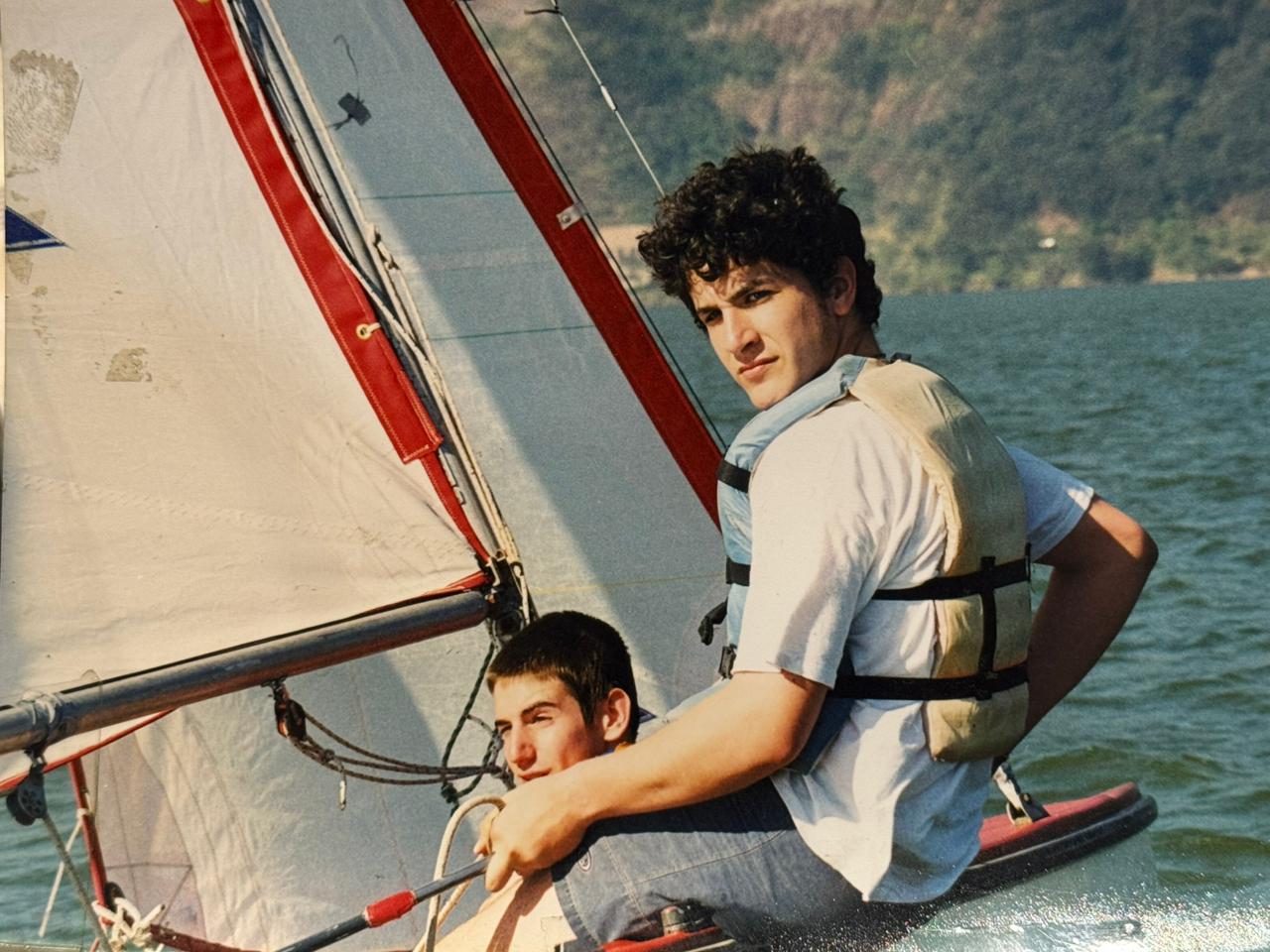

Diego Quiroga, the captain of this sturdy steel sailboat, was born and raised in Ushuaia: one of the most remote places in the world. He’s been a sailor since he was very young—and of course, as the piano that didn’t come aboard and the melodica that travels as a crew member indicate—he’s also a musician. He started sailing at nine years old at one of the two yacht clubs in his city, where he began with an Optimist dinghy, then moved on to windsurfing, and also practiced kayaking and water skiing. A few years later, he continued with Lasers, sailed Pamperos, and also completed courses to become a skipper of both sailing and motor yachts, as well as professional sailing yachts.

“My dad started sailing because of some friends from work, and he would take me out on weekends in a 19-foot sailboat,” he recalls. “I was also lucky that the club was about ten blocks from my house, so every day, from the age of ten, I would hop on my bike and go there. One day, in the back of the workshop, we found an Optimist dinghy: that’s where I started. They told me how it was done, kind of gave me the green light, and I went for it. In ’99, the Sailing School started. That club is still like my backyard,” he acknowledges, laughing.

But Diego’s story didn’t end there: later, at fifteen, he began helping organize scientific expeditions, traveling from ship to ship, sharing mate with the researchers, and observing the preparations for the voyages. “It was also a time when many expeditions to Antarctica began, and when sailors from all over the world started coming to Ushuaia.”

Years passed, and he finished high school. In Bahía Blanca—a city located in the southwest of Buenos Aires Province, 600 kilometers from the capital, on the border between the Pampas region and Patagonia—he studied Marine Biology (so he could go on expeditions) but dropped out, continuing with Geography. Shortly after, he earned his doctorate from the university and trained as a researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET).

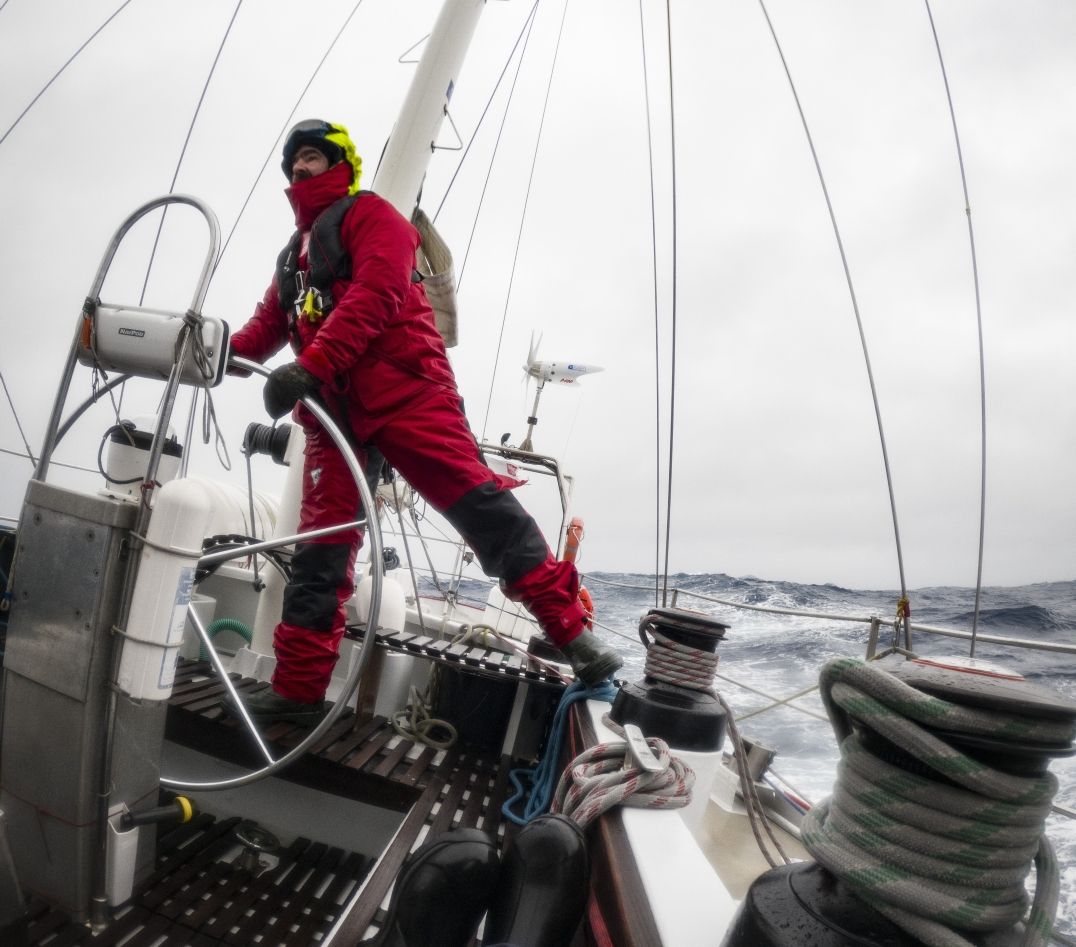

However, the call of the sea proved stronger: he began with short voyages and, in 2014, made his first ocean crossing on the sailboat Ocean Tramp from Punta del Este to Mar del Plata. He also sailed through all the channels of Tierra del Fuego, the Atlantic Ocean, and around Cape Horn, with its icy waters, the region’s unpredictable weather—with strong winds and towering waves—and the aura of stories told by sailors who perished in the Onashaga Channel (in the Yagan language), all accompanied by tales of inhospitable and little-explored landscapes.

In 2017, he undertook his first long voyage as captain: from Puerto Montt (in Chile) to Ushuaia in search of Pic La Lune. In 2019 and 2020, he sailed the Alma Mía from Buenos Aires to Puerto Deseado. In 2022 he participated in an Antarctic expedition with Selma Expeditions and in 2023 in the non-stop Ushuaia-Piriápolis crossing (also in Uruguay). Today he is planning new routes, in addition to being president of the club he loves, that “backyard” that was just a few blocks from his house: the Fuegian Association of Underwater and Nautical Activities (AFASyN).

Interview with Diego Quiroga

Diego, how did this Pic La Lune adventure begin and what possibilities did the sailboat give you to do this type of expedition in Tierra del Fuego?

I was born and raised in Ushuaia. I went to study in Bahía Blanca, but in 2010 I came back for a vacation, and a friend invited me sailing. That’s when I realized I wanted to return to live in my hometown. I started teaching, working at the university, and completed a doctorate and a postdoctoral fellowship. In 2020, with the COVID pandemic, I reevaluated my life and work: because whenever I could, I loved to go sailing.

One day, after much thought, I resigned from all my jobs related to academic activity, and I took a leave of absence from teaching at the University of Tierra del Fuego for a few months. By then, I had already bought the boat and had several expeditions underway, as well as teaching sailing classes at the club.

This entire Beagle Channel region is a destination for sailors worldwide, whether for its proximity to Cape Horn or as a supply port for those who decide to venture into Antarctica. One day, while chatting with one of them on the club’s dock, a man who had traveled to many places, he invited me to go to Antarctica that same week, and I said yes. When I returned from that expedition, I also quit university and focused on doing what I loved most.

How did you come across the Pic La Lune and what kind of instruments does it have on board for these campaigns?

A Spanish couple had been traveling the world: they sailed the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and the South Atlantic. I met them here. When they arrived in Puerto Montt, Chile, they stopped, left their boat ashore, and put it up for sale. When I found out, I contacted them and went to pick it up.

It’s a 38-foot sloop sailboat with a forward cabin, a berth aft, and bunks in the main saloon. It weighs 12 tons. It was built in France in 1995, as an amateur project. It’s designed to accommodate up to four people, but I made some modifications so it can hold six because some expeditions last up to two weeks. It’s comfortable and safe; you can spend several days on board. It has stoves and is perfect for relaxing for several days on a longer voyage. It has radar, satellite communication, internet, VHF radio, AIS, autopilot, a life raft, and a dinghy, as well as personal safety equipment for the entire crew.

Velero “Pic la Lune”

All the way to Puerto Montt?

Yes, it was my first major expedition as captain. But the boat was there, and I had to go and get it. I’d never spent more than three days on a sailboat, and always in fairly sheltered areas or near Ushuaia. Here, suddenly, I was sailing through places I’d never been before: it was a month-long voyage, covering over a thousand nautical miles, on a boat I’d only seen 48 hours before setting sail and that had been out of the water for four years.

Looking back on it now, it was quite risky. I had so little experience that a friend who was on the crew and I miscalculated the food for a month, and between nerves and inexperience, I’d lost eight kilos by the time I got home (laughs). I don’t know, I’d always been a crew member, and here I had to make the decisions as captain. For example, crossing the Gulf of Penas (one of the most difficult places) and having to calculate the weather forecast for that crossing. I think those risks also allowed me to grow a bit more and learn new things.

I imagine the ship has some rigging or features specific to the Patagonian winds, tides, currents, and waves of this region.

Yes, of course, I made some modifications for navigating this region. Anyway, it was built in the 90s, when the focus was on using more durable materials, and it has some oversized features like the double forestay and double fore-and-aft stay. It’s a strong boat.

For example, we have a 100-meter-long anchor chain, 10 millimeters thick, and a 25-kilo delta anchor with an electric windlass. In fact, there are several anchorages where I’ve dropped the full 100 meters, like when we go to Península Mitre (because even though it’s only four meters deep, there’s a 50-knot wind, and just in case, I drop it all).

What other precautions do you need to take in these types of regions?

In those cases, I anchor close to the shore so I don’t create waves and the wind blows from the land. But I’ve been left alone on the boat because people go ashore to do some research for two or three days, and I want to sleep peacefully, eat something, read a book—for that, you need a chain. The same goes for the rigging cables: because we’re used to strong winds and things breaking, here you have to replace them all the time; everything is excessive.

I recently bought a 50-horsepower engine for the boat, which can go 7 knots, but since I’ve been in places with 5-knot currents against me, I have to take some precautions. You can’t go in against the wind or current, and that raises safety concerns when entering or leaving an anchorage. In Tierra del Fuego we also have katabatic winds, which are cold, dense air currents that descend from a high area like a mountain: so, suddenly, you have cycles of 50 or 60 knots for 45 seconds. But you get hit head-on by that wind, and you need the engine to be ready for the ship to respond immediately.

How do nautical charts work in such an inhospitable region?

Chart information is very limited: we have data for the main channels with established routes, but in all other territories or places like the fjords in Chile, navigation is done on a trial-and-error basis. There are several applications like Navionics where you can load updated charts, but then you have to explore on your own because they aren’t current.

However, you start exploring and developing a sense of what you’re navigating simply by looking at the walls, whether they drop straight down, although there are places where I’ve run the boat against the rocks. The same thing happens with katabatic winds: you develop a specific sense for reading them. If you have constant winds of 25 knots and you position yourself downwind of a mountain, for example, they’re bound to blow downwind. So you can predict them to some extent.

It also happens that you anchor and think you’re going to have a west wind, but in front of you there’s a wall, you prepare the lines -because sometimes we anchor with the anchor and two lines to land- and the wind comes in so strong, passes over the mountain that it hits and comes back: then you have 20 knots but constantly.

From what you’ve said, given your training and knowledge, you carry out all kinds of scientific campaigns with the ship, right?

Yes, the possibility of accessing inhospitable areas from a sailboat is important from a scientific point of view. Pic La Lune participated in surveys with marine biologists studying macroalgae or cetaceans, but also with biologists studying terrestrial fauna and birds, oceanographers, geologists, and geomorphologists.

We’ve also collected microplastics, among other science-related activities. I was recently offered the opportunity to lead an expedition for a documentary with archaeologists to visit certain sites. I think the most important thing for these voyages is that they have a purpose.

Why do you think expeditions or journeys have to have a specific purpose?

I’m not interested in tourism-related activities. Since I started in 2022, I’ve focused on organizing campaigns and expeditions, because I made many connections at CONICET (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) and we travel quite a bit to work this way: at least twice a year we go to the Mitre Peninsula, Isla de los Estados, or the Atlantic Coast. We have many projects and ideas to carry out.

Ultimately, the goal is for the trip to have an objective beyond simply seeing the landscapes or the experience of sailing itself. It should impart some concrete knowledge, and that’s achieved by working with people who have prior training, whether it’s through sailing courses or clinics (which are other activities on this sailboat).

Science mobilizes us to certain challenges: for example, I was recently contacted by a group of biologists from Chile to go and work on a colony of cormorants in the Drake Passage (one of the most dangerous routes in the world) or to travel to the Le Maire Strait to record dolphins with hydrophones, so you have to navigate at a certain speed, with a precise course, to record them properly.

How does this search relate to the journey they undertook with Nico Sorín?

Music is always playing on the boat, and there are never any instruments on board. In fact, since there wasn’t room for a piano, I added a melodica. I’m a musician (or at least I try to be). About ten years ago, I sailed a boat to Punta del Este, and on the way back, I stopped in Buenos Aires and went to see Nico Sorín’s band, Octafonic. I bought their CDs and sent him a message because I was listening to that album on my way to the Falklands.

This summer he messaged me about a musical project he was working on in 2024, related to the Arctic and Antarctic Symphonies. I suggested we travel the Beagle Channel from the Mitre Peninsula to the fjords in Chile. The idea was to experience the stark contrast between the two extremes, from the inhospitable and harsh South Atlantic (where the current and winds from Cape Horn converge), the desolation of those lands steeped in stories of ephemeral settlements and shipwrecks, to the fjords themselves. We had a small crew that included an illustrator and a documentary filmmaker.

We were incredibly lucky, too, because we did a lot of walking, sailed with dolphins, played a lot of music (I had brought my guitar and trumpet), and even saw a glacier for 45 minutes of sunlight (after two days of rain, during which it had been completely covered). It was like a dream: like the curtain rising on a stage. Nico is now finishing the arrangements for about twelve songs. This experience, going back to the topic we were discussing earlier about tourist excursions, reaffirms what I was saying before: that trips have to have a purpose, that they fulfill and satisfy me.

Finally, Diego, what are your upcoming projects?

We always have ideas and projects in mind that we hope will come to fruition. A year and a half ago, I bought another boat, a 15-meter vessel with three cabins, two bathrooms, and room for nine people. It’s a 1979 boat, built in Italy, and the plan is to leave the canal and travel to other places like the Falkland Islands. It’s called La Pinta (but I’m going to change the name).

I also dream of going to South Georgia (a friend just arrived from there), and starting to travel to Buenos Aires. Some time ago, I took a boat to Piriápolis, and in thirteen days we were there (in Uruguay), and in two weeks, perhaps, I imagine, we could be in Brazil. The experience with Nico Sorín also led me to think that music could be part of the project, as well as the entire audiovisual component, which was something I hadn’t considered until now.

The plan, anyway, is to start experiencing the sea a little more: a place where I can connect and think differently, where I believe you vibrate on a different frequency.

Links of interes:

Site: https://piclalunesailing.com/

From “Navegantes Oceánicos”, we thank Diego Quiroga for sharing his experiences at sea and explorations aboard the ocean-going sailboat “Pic la Lune” with our readers in this engaging interview.

Best of luck and fair winds on your upcoming voyages and projects!