Introduction.

In the first chapters of this online book, “Sail Handling and Trim,” we examined the theoretical fundamentals of sailing in some detail, and then applied these principles to trimming the headsail (the genoa or foresail), from a more practical perspective.

Before delving into this new chapter, it is advisable to review those theoretical fundamentals, especially the importance of the angle of incidence and the sail shape (position and size of the sail’s leech) for proper trim. You can find this information in the following link: “How to Trim a Sail?”.

In this new chapter, we will study the mainsail in detail. As you probably know, this is the sail that offers the greatest potential for adjustment, since it has more control elements that we can manipulate, as shown in the following diagram.

To this end, throughout this chapter we will examine in detail the eight control elements we have for this sail, and discuss how to adjust them under different wind conditions.

The eight control elements of a mainsail are:

1) Backstay tension.

2) Cunningham tension.

3) Halliard tension.

4) Boom vang tension.

5) Clew position.

6) Main sheet tension.

7) Mainsheet traveler position.

8) Boom outhaul tension.

It is important to note that the first five control elements listed here primarily affect the shape of the sail, and allow us to modify, in some way, the position and depth of the sail’s leech. We will examine this in detail. Once these controls are initially adjusted, they are used less frequently on a cruising sailboat, and are, of course, adjusted much more precisely and frequently on a racing sailboat.

The sixth control, the main sheet, is the one most frequently used in any case, and allows us to maintain the correct angle of attack of the apparent wind, by hauling in or letting out the sheet, when the wind direction or the boat’s course changes.

Finally, we will discuss the last two controls, the main sheet traveler and the boom outhaul, which, among other things, allow us to adjust the twist in the upper part of the sail, under different wind conditions.

Furthermore, even if our sailboat’s mainsail does not have all eight of the control elements mentioned, understanding how they work will help us make better use of the sail trim options available on board. Efecúe Log In para desbloquear.Este contenido solo está disponible para subscriptores de navegantesoceanicos.com

Control elements for the main sail.

1) Backstay tension.

Adjusting the tension of the after backstay has a different effect on a full-rigged sloop rig compared to a fractional sloop rig. For an introduction to this topic, you can find more information here: Types of sailboat rigs.

In a full-rigged mast setup, the tension in the backstay is directly transferred to the tension in the forestay, and its primary effect on sail trim is on the headsail (the genoa or the jib), as we saw in the chapter: Trim of the Headsail (I). Control Elements.

However, in a fractional rig, as shown in the figure above, increasing the tension in the backstay, in addition to increasing the tension in the forestay, produces an even more important effect: it flexes or bends the mast aft, which alters its shape and allows for more adjustments to the mainsail. Let’s look at the two examples in the figure:

a) With the backstay looser, the mast bend decreases and the sail’s leech shape becomes fuller, so we gain power, although we will have less ability to sail close to the wind (due to the increased angle of attack). We will usually loosen the backstay when sailing with broader angles of approach (aft of the beam) or in light winds.

b) When we increase the tension in the backstay (case b in the figure), the mast (and consequently the leech of the mainsail) will have greater curvature, and the sail as a whole will flatten. The leech shape becomes flatter and the angle of attack decreases, and therefore we will have less power, but more ability to sail close to the wind with a tighter angle to the wind. We will keep the backstay tighter when sailing upwind in strong winds.

Many cruising sailboats do not have a readily adjustable backstay, nor adjustable shrouds. In this case, it is advisable that when we adjust the standing rigging, both the forestay and the backstay are kept taut, so that the boat is always ready to sail in strong winds.

2) Cunningham

The Cunningham purchase is a rigging system used to tension the lower edge of the main sail. This system works by pulling on a fitting located above the tack point, which is commonly called the “Cunningham fitting”

The Cunningham line has the same effect as the main halyard; that is, it pulls the leech of the sail forward when tensioned, as we will see later.

However, since the tension of the halyard has less effect on the lower part of the sail’s leech, the Cunningham line is more effective precisely in that lower section. The Cunningham line is typically used when sailing in strong winds and rough seas.

3) Halyard tension and cunningham.

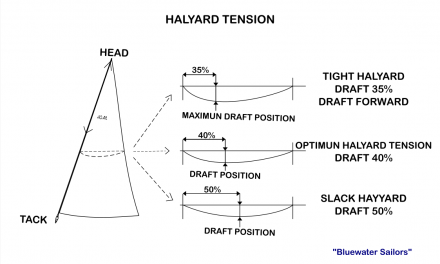

By increasing or decreasing the halyard tension (or using the Cunningham), the effect on the mainsail is to move the position of the leech (the point of maximum sail depth) forward or backward.

The most appropriate mainsheet tension, with moderate winds, is that which places the leech approximately 40% of the way down the halyard, as shown in figure b) above. Depending on the sail, the optimal leech position can vary between 40% and 50%.

When hoisting the mainsail for the first time, it is recommended to visually check the leech position and adjust the mainsheet tension accordingly. A good practice is to mark the halyard at this position, so that you can hoist the sail to this point on subsequent occasions.

Excessive mainsheet tension should be avoided, as it will cause vertical wrinkles near the luff of the sail. These vertical wrinkles should be avoided because they will create turbulence in the windward area of the sail. On the other hand, a sail that is not hoisted tightly enough may have horizontal wrinkles, which should also be avoided, although they are less critical.

– Increasing the mainsheet tension (or the Cunningham, if it is also adjusted), as shown in case a) of the figure, moves the leech position forward to approximately 30%. This concentrates the sail’s driving force on the more efficient forward part of the sail and also reduces leeway. The angle of attack increases (although the angle of heel will also increase), thus increasing the driving force. It is worth noting that with a leech position further forward, we will have better tolerance for steering errors when changing course. We will tighten the mainsail halyard more when sailing upwind in strong winds or rough seas.

– Decreasing the mainsheet tension (or the Cunningham, if it is also adjusted) has the effect of moving the leech position aft, as shown in case c) of the figure above. The angle of attack will decrease, allowing us to sail closer to the wind, although at the cost of some driving force. This is a good measure for sailing upwind in very light winds.

4) Flattering reef.

The Cunningham reefing system (or flattening reef) is a type of rigging that uses a cleat or fitting located just above (approximately 20/30 cm) the clew of the sail.

This system works by pulling down on the clew of the sail, thus flattening the lower part and improving the boat’s ability to sail close to the wind.

The flattering reef is a common feature on cruising yachts and is particularly useful when the sails are worn and have lost their shape, making it difficult to maintain the desired sail shape for efficient performance when sailing upwind.

4) Clew outhaul.

The clew outhaul is a piece of rigging used to move the clew of the main sail forward or aft. This movement, depending on the tension in the outhaul, will affect the shape of the sail, particularly in its lower section.

a) With a very tightly trimmed clew outhaul, as in case a) of the figure above, the sail flattens, the position of the sail’s draft (or deepest point) shifts slightly aft, and the angle of incidence decreases. Tightening the clew outhaul is generally useful for improving the boat’s ability to sail close to the wind.

b) With a looser clew outhaul (case b) of the same figure), the draft (or deepest point) of the sail increases, and its position shifts slightly forward. This results in greater sail power and better control of the boat. The angle of incidence also increases. Loosening the clew outhaul is typically used when sailing on a broad reach or with more open wind angles.

6) The mainsheet

The mainsheet is the primary control line for any sail, including the main sail.

It will need to be constantly adjusted with even the slightest change in wind direction or the sailboat’s course, whether it’s a cruising vessel or, even more so, a racing yacht.

The function of the mainsheet is to maintain the correct angle of incidence between the leech of the sail and the relative wind, in order to maximize the sail’s performance (achieving maximum driving force). The diagram shows a situation where the boat is drifting off course to leeward, and how we adjust the mainsheet to maintain the correct angle of incidence.

As we have seen in previous chapters, the correct way to trim the mainsheet (with the relative wind coming from abeam or forward of the beam) is very simple:

Ease the mainsheet until the sail starts to luff, and then stop easing. Then, gently pull in the mainsheet, just enough to eliminate the luffing.

The effect of pulling in (or easing out) the mainsheet is immediate and direct, since the driving force is proportional to the angle of incidence (which is directly related to the fullness of the sail). Therefore, by increasing this angle of incidence, without exceeding the point where the sail starts to luff (losing the Venturi effect), the driving force will increase.

With this method of trimming the mainsheet, when sailing upwind, we will use the maximum possible angle of incidence to generate the greatest possible driving force, while maintaining a smooth airflow over both the windward and leeward sides of the sail.

7) The position of the mainsheet traveler

The traveler is a piece of rigging to which the mainsheet is attached, and it can be moved laterally from the centerline to either port or starboard. We typically refer to the movement of the mainsheet traveler as being towards the windward or leeward side. We usually use the mainsheet traveler when sailing upwind to adjust the twist of the sail at its upper edge.

– As we can see in the diagram above (on the left), by easing the mainsheet and moving the traveler car windward, we maintain the same sail trim, but increase the twist at the top of the sail. This will give the sail more power, and I will use this method of increasing twist when we are sailing upwind in light winds.

– To decrease the twist, when sailing upwind in strong winds, I will do the opposite, as shown on the right side of the diagram. I will move the traveler car slightly leeward and pull in the mainsheet.

Another common use of the traveler car is when sailing upwind in gusty winds. If a gust suddenly hits us, we can quickly move the traveler car leeward, and the mainsail will lose some power. When the gust subsides, we move the traveler car back to its optimal position.

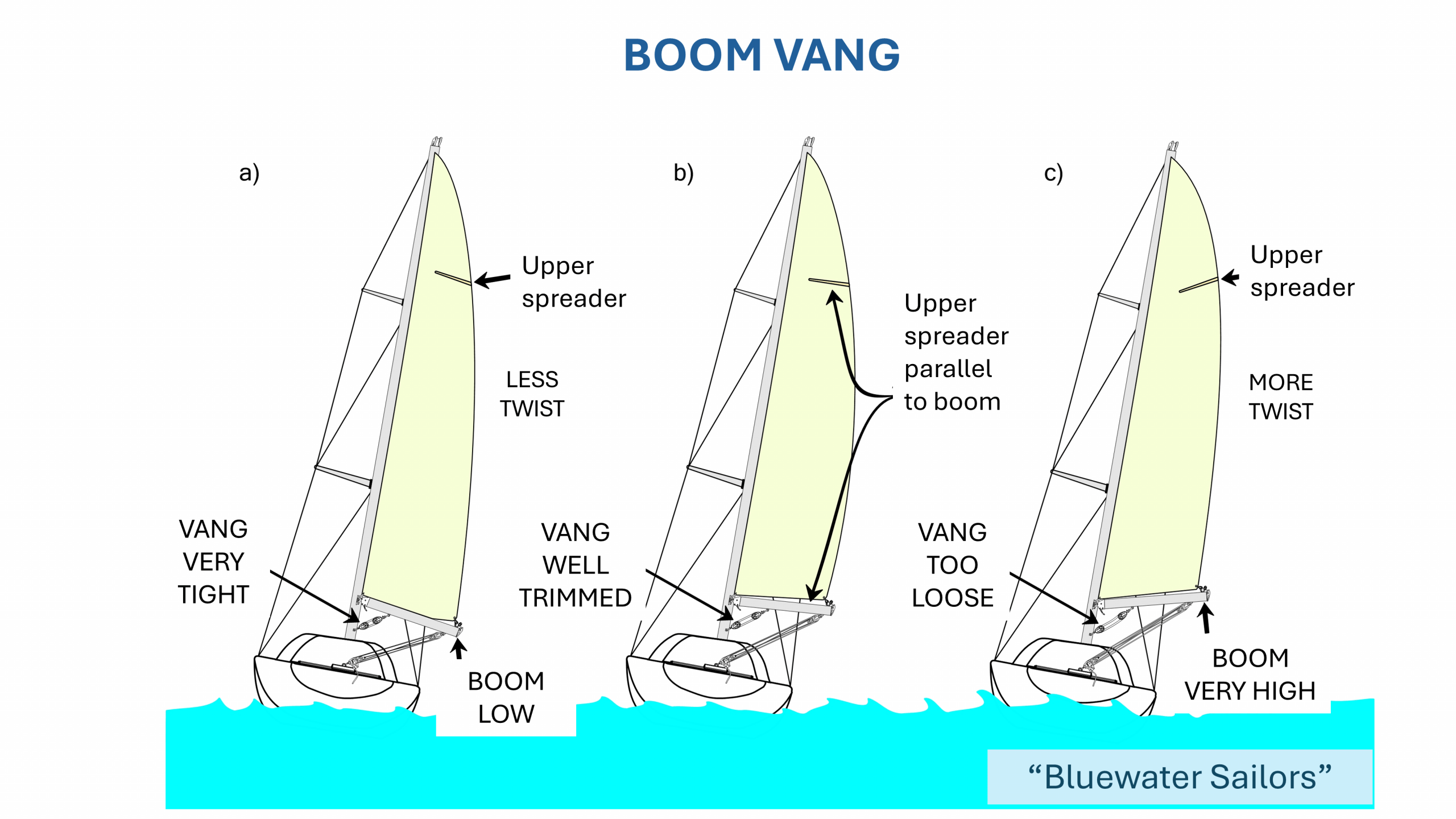

7) The boom vang

The boom vang (also called the kicking strap) has the function of controlling the height of the boom. By pulling on the vang, the boom is pulled downwards, and consequently, the foot of the sail is also pulled down.

When sailing on a very tight reach, with the mainsheet hauled down hard and practically taut, the mainsheet itself already pulls the boom down, and the backstay may not be necessary.

However, with broader reaches, as the mainsheet is eased, the boom will tend to rise, and that’s when it’s more important to tension the backstay. With broader reaches, the backstay also helps to control the sail twist, as we can see in the diagram above:

a) With the vang very tight, as shown in case a) of the diagram, the boom (and the boom vang) is lower, and consequently, the sail twist is reduced.

b) A properly tensioned vang can be seen in case b), where the boom forms a 90-degree angle with the mast and the upper spreader is parallel to the boom.

c) With the vang too loose, as in case c), the boom will be too high, increasing the sail twist.

Final considerations

This chapter has described the eight (8) main control lines for the mainsail, along with some general guidelines for adjusting them depending on the wind conditions. We have seen how trimming the first five control lines allows us to adjust the shape of the sail (size and position of the leech), and that the remaining lines also allow us to adjust the angle of attack and the twist of the sail.

Although it may seem complex, understanding the individual effect of each control line will allow us to practice at sea and become familiar with them. As we gain experience, combining all the available control lines on our sailboat will make it easier to properly trim the mainsail in any given situation.[/ihc-hide-content]